Initial participants in the framework include major economies like Australia, India, Japan and South Korea as well as developing ones, including Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam.

Get more news Live May 23, 2022, 7:15 AM UTC / Updated May 23, 2022, 11:09 AM UTC By Alex Seitz-Wald , Elyse Perlmutter-Gumbiner and Jennifer JettWASHINGTON — President Joe Biden on Monday announced an economic agreement with a dozen other countries aimed at countering China’s influence in the Indo-Pacific, but which critics say may come as too little, too late to achieve that goal.

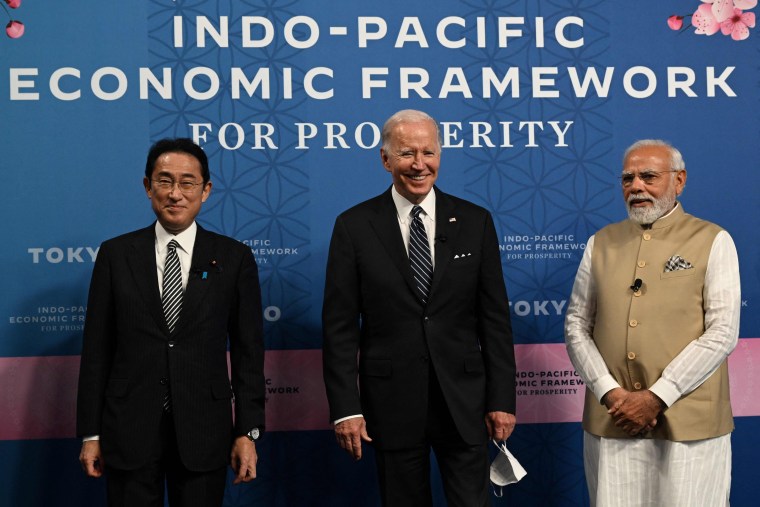

“The future of the 21st-century economy is going to be largely written in the Indo-Pacific, in our region,” Biden, in Tokyo on the second leg of his first presidential trip to Asia, said at a launch event for the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity.

“The nations represented here today and those who will join this framework in the future are signing up to work toward an economic vision that will deliver for all our people,” Biden said, “a vision for an Indo-Pacific that is free and open, connected and prosperous, and secure as well as resilient, where economic growth is sustainable and it’s inclusive.”

Along with the United States, initial participants in the framework include major economies — like Australia, India, Japan and South Korea — as well as developing ones, including Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. They also include smaller countries like Brunei, New Zealand and Singapore.

Together, they represent about 40 percent of global gross domestic product, administration officials said.

“It is by any count the most significant international economic engagement that the United States has ever had in this region,” Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo told reporters ahead of the announcement.

The pact is about “restoring U.S. economic leadership in the region” and “presenting Indo-Pacific countries an alternative to China’s approach,” she added.

But critics say the framework is a belated and insufficient attempt to make up for America’s longtime lack of economic strategy in the region, a vacuum that has been filled by China.

Van Jackson, an American scholar of international relations at Victoria University of Wellington in New Zealand, called the framework “a slogan without a purpose.”

“We’ve been kind of derelict on economic policy,” he said. “This whole P.T. Barnum show around the framework is supposed to address that or show that we’re doing something about it, but when you peel back the onion none of the things that the region cares about are really there.”

The Biden administration’s relative lack of economic engagement in the region up to this point stands in contrast to its robust security efforts, including a new security pact with Australia and Britain and a greater focus on the Quad, an informal security grouping made up of the U.S., Australia, India and Japan.

Earlier on Monday, Biden commended Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s plans to strengthen his country’s defense capabilities and said the U.S. would support Japan becoming a permanent member of the U.N. Security Council. While in South Korea on the first part of his trip, Biden also said he and President Yoon Suk-yeol would discuss expanding joint military exercises.

Many Asian governments see the U.S. as an important security counterweight as China seeks to project greater strength around the region. But while Asian economies still seek access to the U.S. as an export market, they have largely relied on China as their engine of growth since the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, Jackson said.

“This framework is not on trend with the region,” he said, though its symbolic nature also means it costs governments nothing to join."

China, the top trade partner for most of the countries participating in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, has criticized it as intended to sow division, with Foreign Minister Wang Yi saying on Sunday that it was bound to fail.

Biden administration officials said the deal would focus on four “pillars” — supply chain resiliency, clean energy and decarbonization, tax and anti-corruption, and enhanced trade.

Speaking to reporters on Sunday, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan differentiated the framework from past trade deals, such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP, another pact meant to counter China that was negotiated during the Obama administration.

That deal faced opposition from both the left, especially organized labor, and the right, largely from the GOP’s growing nationalist wing. President Donald Trump pulled out of the TPP shortly after he took office in 2017, effectively killing it.

“Our fundamental view is that the new landscape and the new challenges we face need a new approach, and we will shape the substance of this effort together with our partners,” Sullivan said.

Led by Japan, the 11 other countries that were in the TPP signed a successor agreement called the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, or CPTPP, which China is trying to join.

Several countries in the CPTPP, like Mexico and Canada, are not included in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, which Sullivan said includes a wider range of countries.

“You’ve got major economies, emerging economies, economies with which we have free trade agreements and others for which this will be the United States’ first economic negotiation,” Sullivan said.

Susannah Patton, head of the Power and Diplomacy Program at the Lowy Institute in Sydney, said the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework is a response to a “political problem”: The U.S. is not a member of either the CPTPP or the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a free trade agreement among 15 Asia-Pacific nations including China, Japan and South Korea. Nor is it likely to join either agreement anytime soon.

While the framework is a way for the U.S. to show it is still engaged in the region economically, Asian governments hope it will serve as a placeholder until domestic politics allow Washington to sign on to something more concrete, Patton said.

At a joint news conference on Monday, Kishida reiterated Japan’s desire for the U.S. to rejoin the TPP.

Unlike the TPP, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework is more of a general regulatory agreement, Patton said, and it appears that countries do not necessarily have to commit to all of it.

“That could mean that the U.S. is able to potentially tap into a broader range of partners, but it also might make it harder to apply pressure on countries to do what the U.S. would like them to do” in terms of environmental, labor and other regulations, she said.

Leaders still need to negotiate the details of the framework, which Patton said was basically an “initial show of interest” by the participating countries.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean that the countries that sign up now are the ones who are going to be making substantive commitments down the track,” she said.

Alex Seitz-Wald is a senior political reporter for NBC News.

Elyse Perlmutter-GumbinerElyse Perlmutter-Gumbiner is the coordinating producer for the NBC News White House unit.

Jennifer Jett is the Asia Digital Editor for NBC News, based in Hong Kong.